Artist’s Reception

Thursday, 10 December 2015, 6 to 8pm

Special Gallery Talk (Jewellery Artist Mimi Lipton together with Master Goldsmith Nan Nan LIU Moderated by Yim TOM)

Saturday, 12 December 2015, 3 to 4.30pm * The talk will be conducted in English

Exhibition Period

10 December 2015 – 16 January 2016

Presented by

Hanart TZ Gallery in Collaboration with Fabio Rossi

Hanart TZ Gallery

401 Pedder Building, 12 Pedder Street, Central, HK

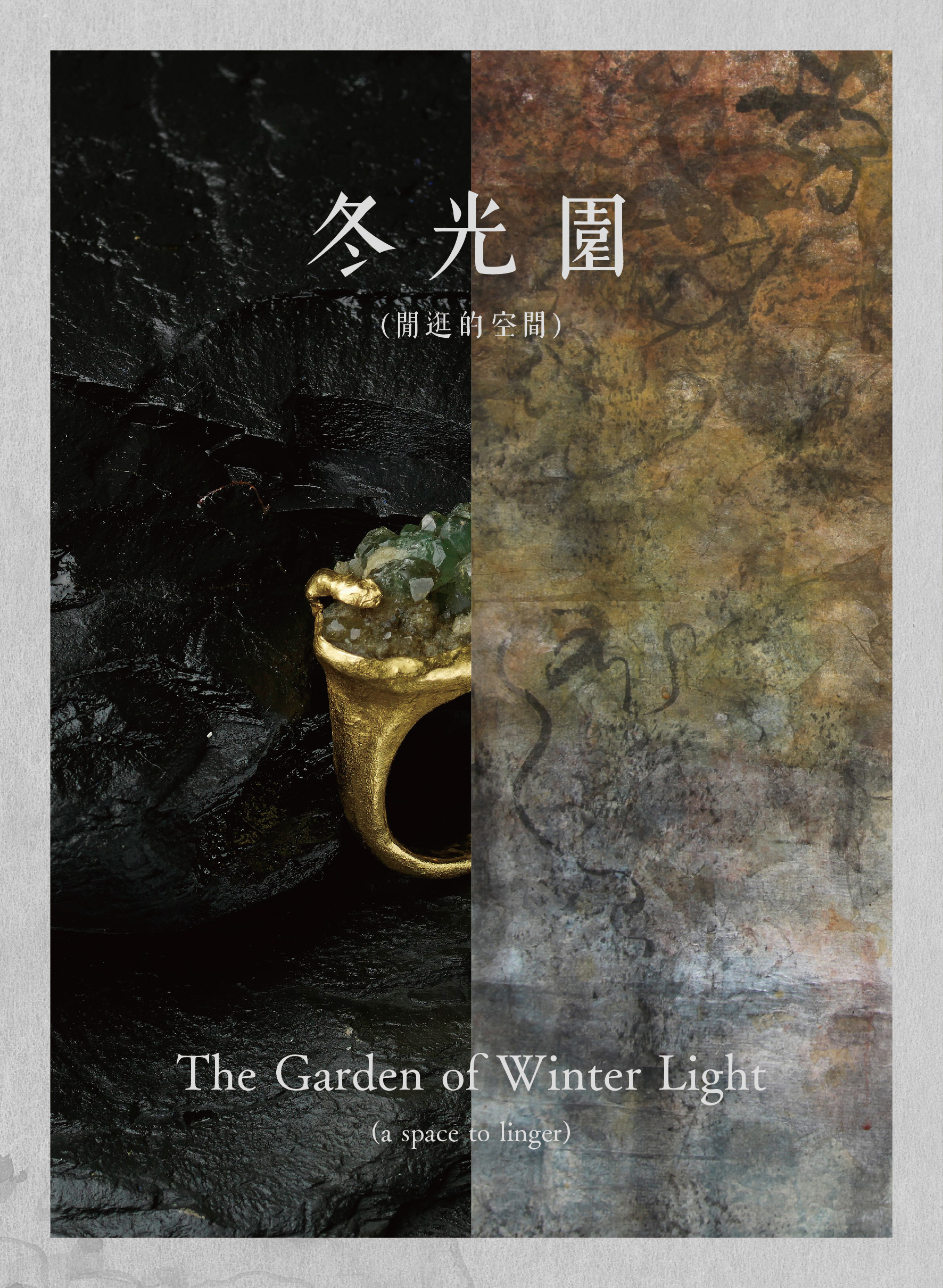

The Garden of Winter Light (a space to linger)

Paintings by 繪畫

CHENG Tsai-Tung, Gade, LIE Fhung, TSENG Yu-Ho, Dagvasambuugiin UURIINTUYA, WANG Chuan, WANG Dongling, WONG Chung-Yu, XU Longsen, YAN Shanchun, YU Peng

鄭在東、Gade、李楓、曾佑和、Dagvasambuugiin UURIINTUYA、王川、王冬齡、黃琮瑜、徐龍森、嚴善錞、于彭

Sculptural Objects, Assemblages by 立體作品

FUNG Ming Chip, LEE Man Sang, Nortse, XU Guodong, and 13th-15th Century Tibetan Artists

馮明秋、李文生、Nortse、徐國棟、西藏佛教古物

Jewellery by 珠寶

Mimi LIPTON

Environment Design by 展場設計

LEE Man Sang 李文生

Curated by 策展人

Valerie C. DORAN任卓華

Presented by 協辦

Hanart TZ Gallery in Collaboration with Fabio Rossi 漢雅軒 與 羅西

Curatorial Essay

Art as a Place (Maybe a Garden)

Valerie C. Doran

The Garden of Winter Light (a space to linger) is in essence an atmospheric intervention in a ‘white cube’ gallery space. Its structure (in both a physical and metaphysical sense) emanates from the resonance and consonance that emerges from the combined presence, or sounding, of an eclectic mix of artist’s voices within an (eclectically) reconfigured environment. This environment was collaboratively designed with the wonderful Hong Kong artist Lee Man Sang, whose artistic practice includes sculpture, assemblage, invented musical instruments and other artistic makings more hard to define.

The curatorial approach was inspired by a theoretical concept developed by Johnson Chang Tsong-Zung, Gao Shiming and Qiu Zhijie, and which they have applied to two previous exhibitions (Taipei 2005, Shanghai 2006). Called the ‘Yellow Box’, this theory examines elements of traditional Chinese literati (scholar-artist) aesthetics and the way these can be applied to a contemporary context, in particular as regards the literati way of engaging with art in an environment. The traditional space of literati gatherings was either in a garden or a studio—a space to linger—where guests met to drink tea or wine, admire scroll paintings and calligraphy (and perhaps add their own colophons), play or listen to music, and enjoy objets d’art (often called ‘scholar’s playthings’). These were often antiquities, or sculptural pieces that incorporated objects which were brought directly out of wild nature and into culture: for example the scholar’s rock which is basically a found natural object that becomes an art object when it is mounted on a stand. In a contemporary context, the Yellow Box is both a response to, and a potential intervention in, the neutralized space of the modern gallery or exhibition hall.

The Garden of Winter Light is meant to reflect the idea of a conceptual garden, a space that is embracing and invites lingering. Since the show is taking place in December—both the height of winter and, in many cultures, the season of spiritual light—the artwork ‘reflects’ certain associative qualities, and references three of the Five Elements of Chinese cosmology—metal, water, and earth—which are related to autumn and winter and the shift between the seasons. The connection to these elements in the artworks is sometimes material, sometimes visual and sometimes allusive.

The Garden of Winter Light is not meant to be a stage set imitating the past but something real in itself and authentic to this moment. The fact that this ‘garden’ is coming into being in a contemporary art gallery, in an urban setting, means inevitably that there are more problematized contemporary sensibilities involved: for example, while much of the art celebrates the link to nature, sometimes it is about the incursion of contemporary culture into nature, and the loss of balance.

In curating the show I had the opportunity to select from the collections of both Hanart TZ Gallery and Fabio Rossi, encompassing artists across different generations and different worlds. The element of water, associated with winter, also represents the flow of time, and in this space one is moving through time, encountering moments of artistic creation spanning centuries as well as decades and geographies, from 13th century Tibet to early 1990s Taiwan to present-day Hong Kong, Mongolia and elsewhere. This eclecticism is part of the unfolding of small journeys within this space. One of the essential things that connects the works is an inner/intra resonance and refraction grounded in a concern with that interface between culture and nature which so captivated literati aesthetics; and also with culture itself when it too is natural—when it grows and adapts and transforms without losing its source-root.

Central to the aesthetic and material environment, and an unusual aspect of it, is the presence of the frankly stunning work of London-based independent jewelry designer Mimi Lipton, who has been collecting raw gems, shells, coral and other natural objects from her travels around the globe for many decades. Mimi collaborates with artist-goldsmiths to produce sculptural pieces of jewelry that represent her own version of that interface between wild nature and culture. Many of the pieces are mounted and sculpted in such a way that they seem like small universes unto themselves, in much the same way that a scholar’s rock does.

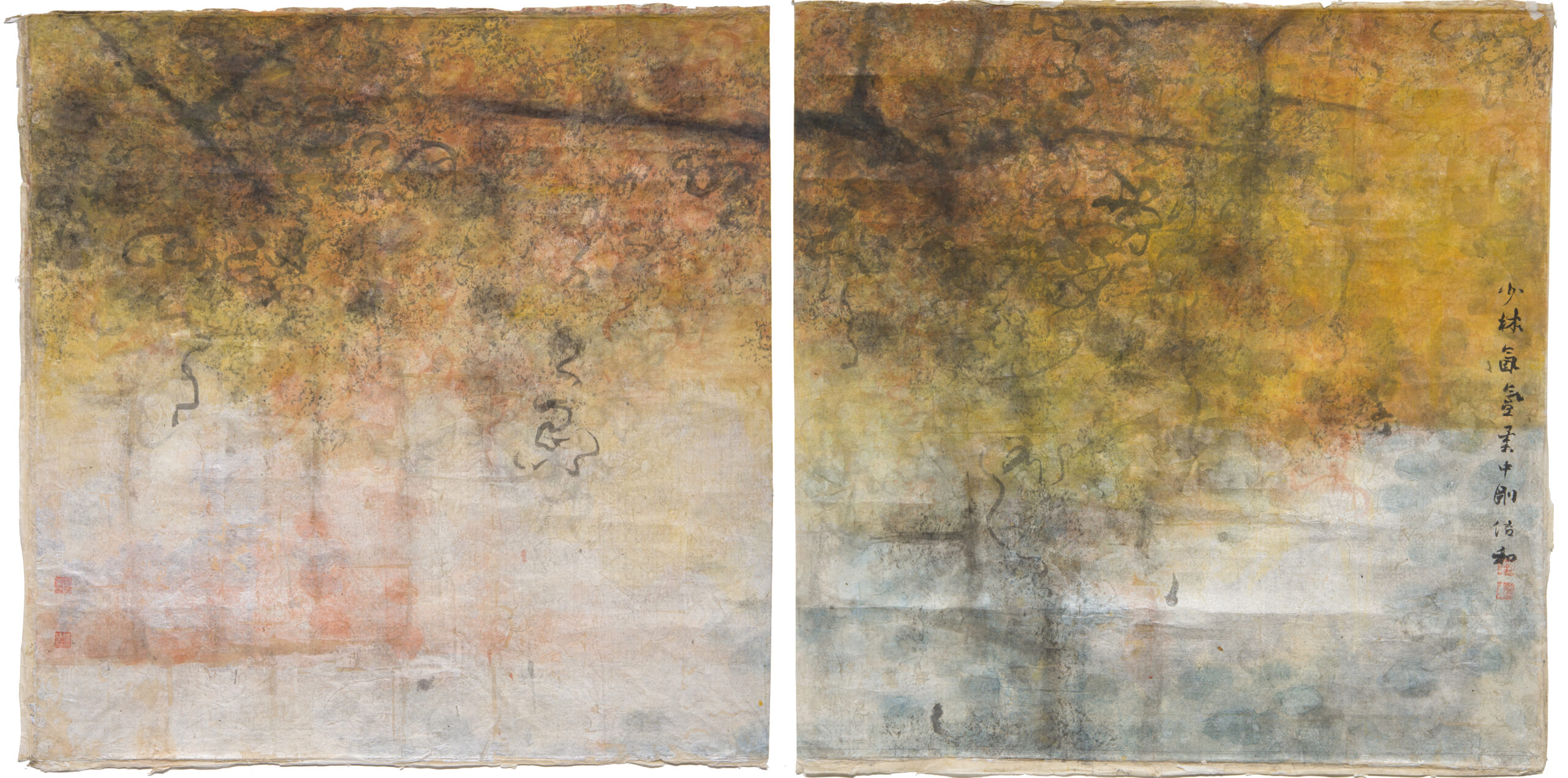

Reflecting the aura of the rare and precious is a luminous mixed-media diptych by Tseng Yu-Ho (one of the first ink painters to experiment with using traditional materials in unorthodox ways), which exemplifies her unique ‘dsui-hua’ technique, in which the paper itself is also used as an expressive, painterly medium. This is a rare work and a centrepiece of the exhibition.

Mongolian artist Dagvasambuugiin Uuriintuya’s deceptively ornate landscapes, almost tapestry-like in their textural richness, are marked by a striking dichotomy of delicacy and power as she reveals the heart and bones of the mountains and the visceral human presence therein. Mainland Chinese artists Yan Shanchun and Wang Chuan each uses a distinctive language to create semi-abstract paintings that hold the gaze on small scenes within nature—whether a lotus pond in Hangzhou or a fish floating beneath a tangled reed─to reveal the luminous energy shining within nature’s seemingly random patternings. Beijing-based ink painter Xu Longsen, known for his soaring, monumental landscapes, here is represented by a group of smaller-scale, delicate works in ink-and-colour on gold paper that are like fractals holding the entire presence and weight of the mountains.

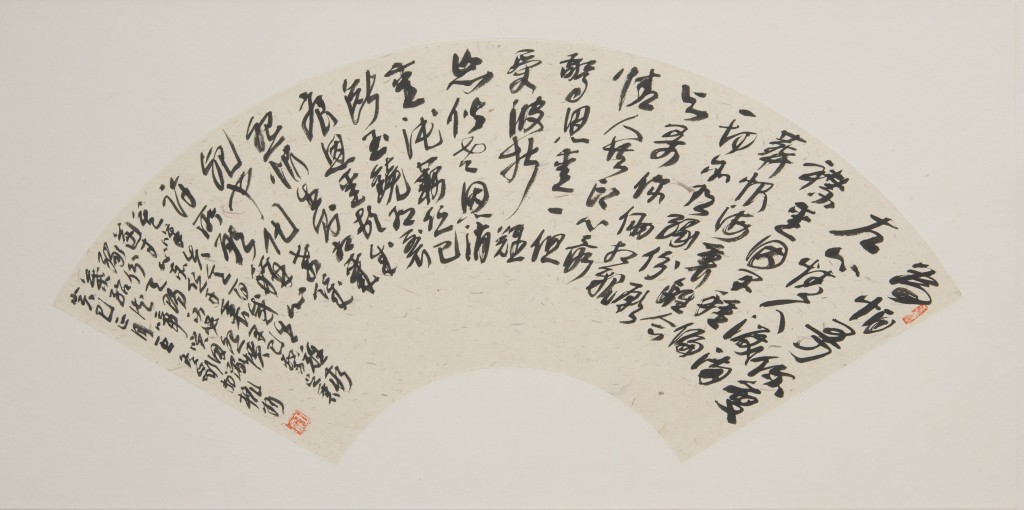

The revered calligrapher Wang Dongling, who for the last decade has focused on monumental calligraphic installations of passages from the Chinese classics and Buddhist sutras, is by contrast represented here by a bit of whimsy, a fan inscribed with the lyrics to a popular Chinese song.

Two works by calligrapher and seal carver Fung Ming Chip, created two decades apart, reveal different facets of the artist’s deeply conceptual sensibilities: his monumental carved ‘seal’ in wood and acrylic contains quirky calligraphic forms that look almost animated, as though they were ready to walk out of the frame, while his ‘time-based’ calligraphy communicates simultaneously the qualities of appearance and disappearance.

Chinese-Indonesian artist Lie Fhung’s abstract landscapes executed in mixed media on copper represent another kind of interface between culture and nature: the artist’s elegant compositions are a result of using organic interventions to alter the oxidation process of the copper, after which she sets the metal aside for several months to allow the imagery to evolve naturally, before intervening again. Reflecting a more traditional form of this intervention into nature are the scholar’s rocks of sculptor Xu Guodong, who continues an ancient tradition of ‘working’ natural stones to enhance the forms that originally sculpted by the tools of wind, water and time.

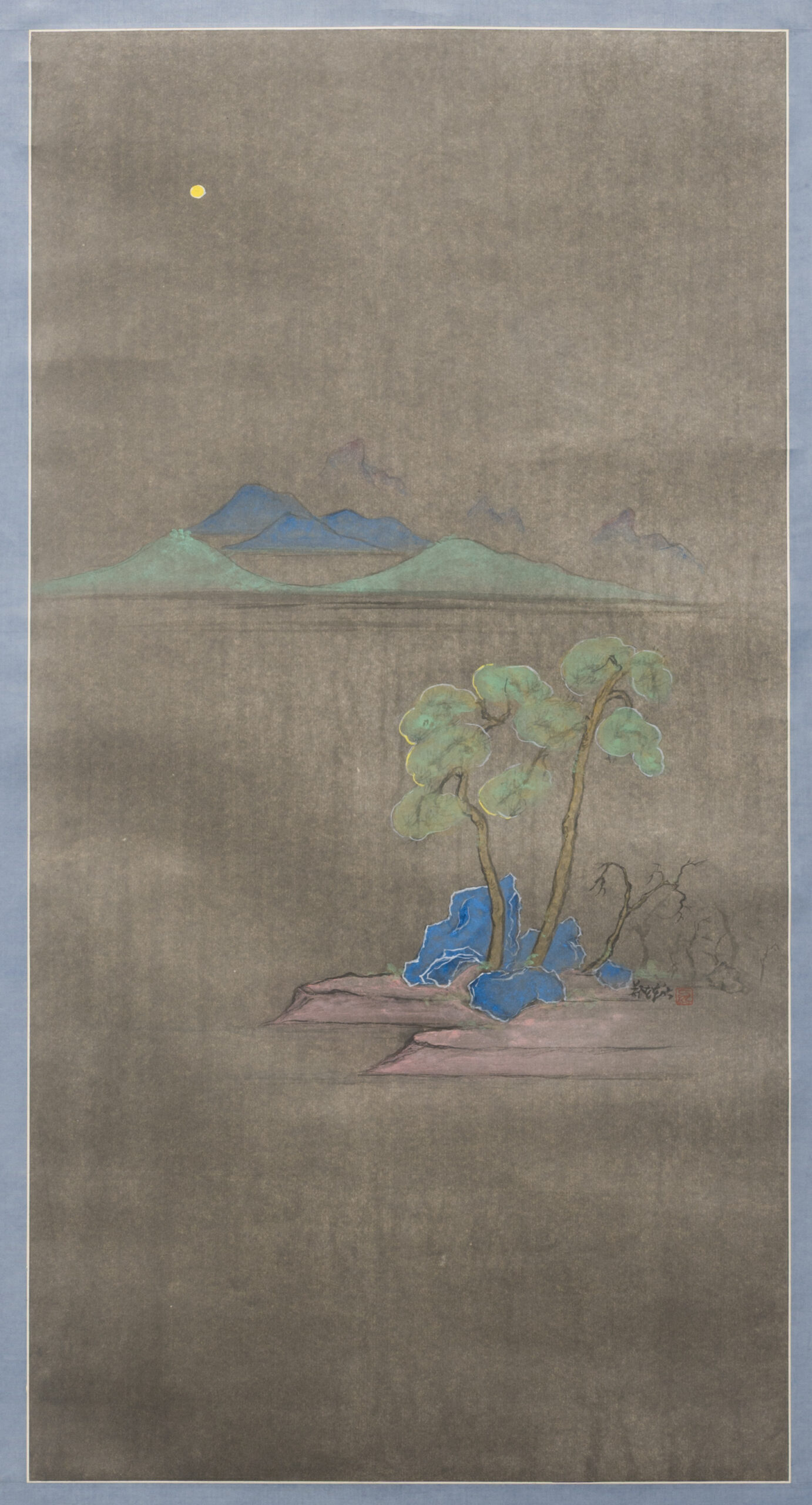

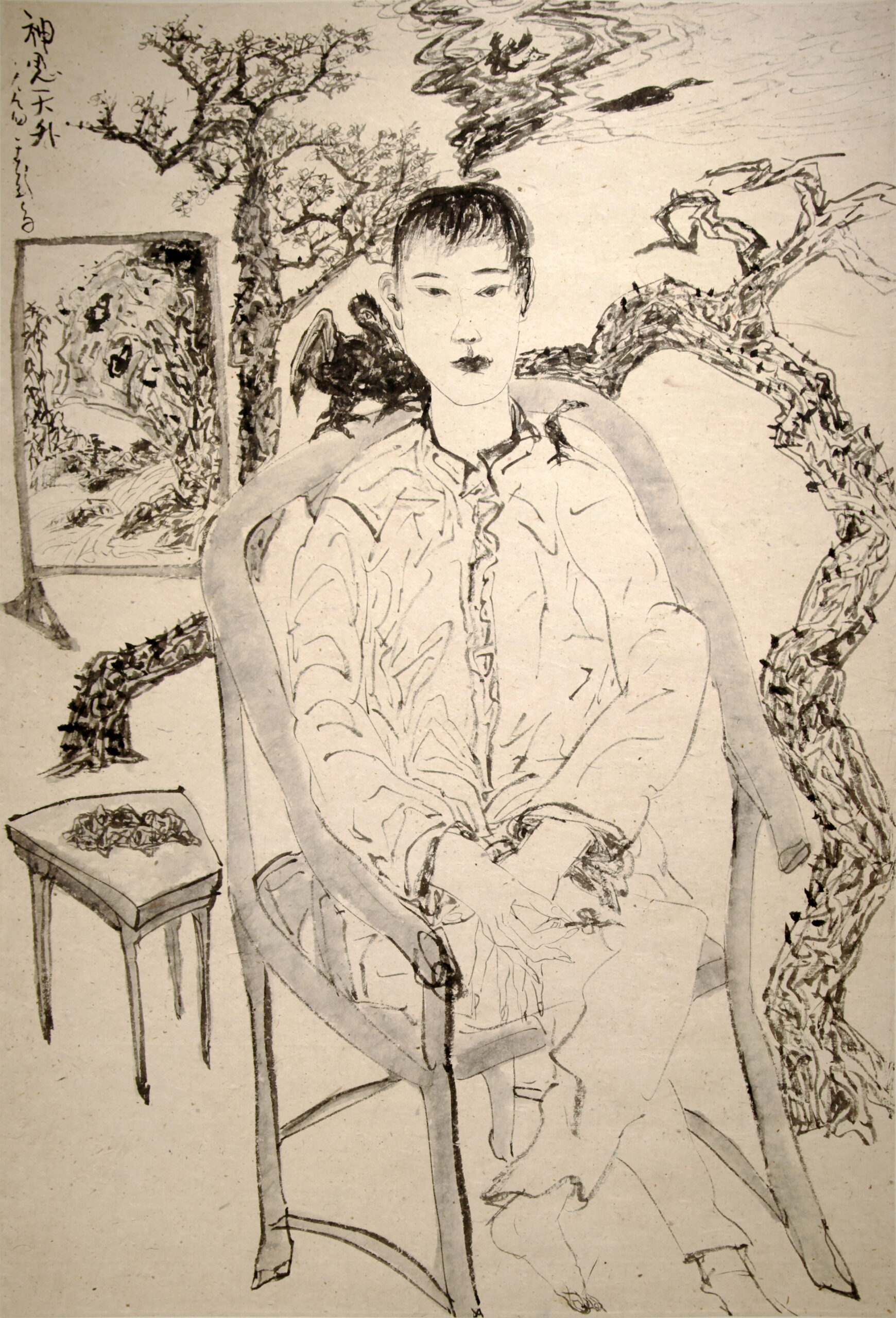

The wild, dynamic energy of the eccentric Taiwanese ink artist Yu Peng (who sadly passed away last year) manifested in visions of his own life in contemporary Taiwan set amidst fantastical gardens that he painted on everything from little wooden boxes to large scroll paintings to the ceiling of his house (we do not include the ceiling in the present show). The flaneur sensibility of Yu Peng’s contemporary, Cheng Tsai-Tung, is captured in the expressionistic language of his ink painting of a silvery night landscape that manages at once to be austere and decadent, romantic and ironical.

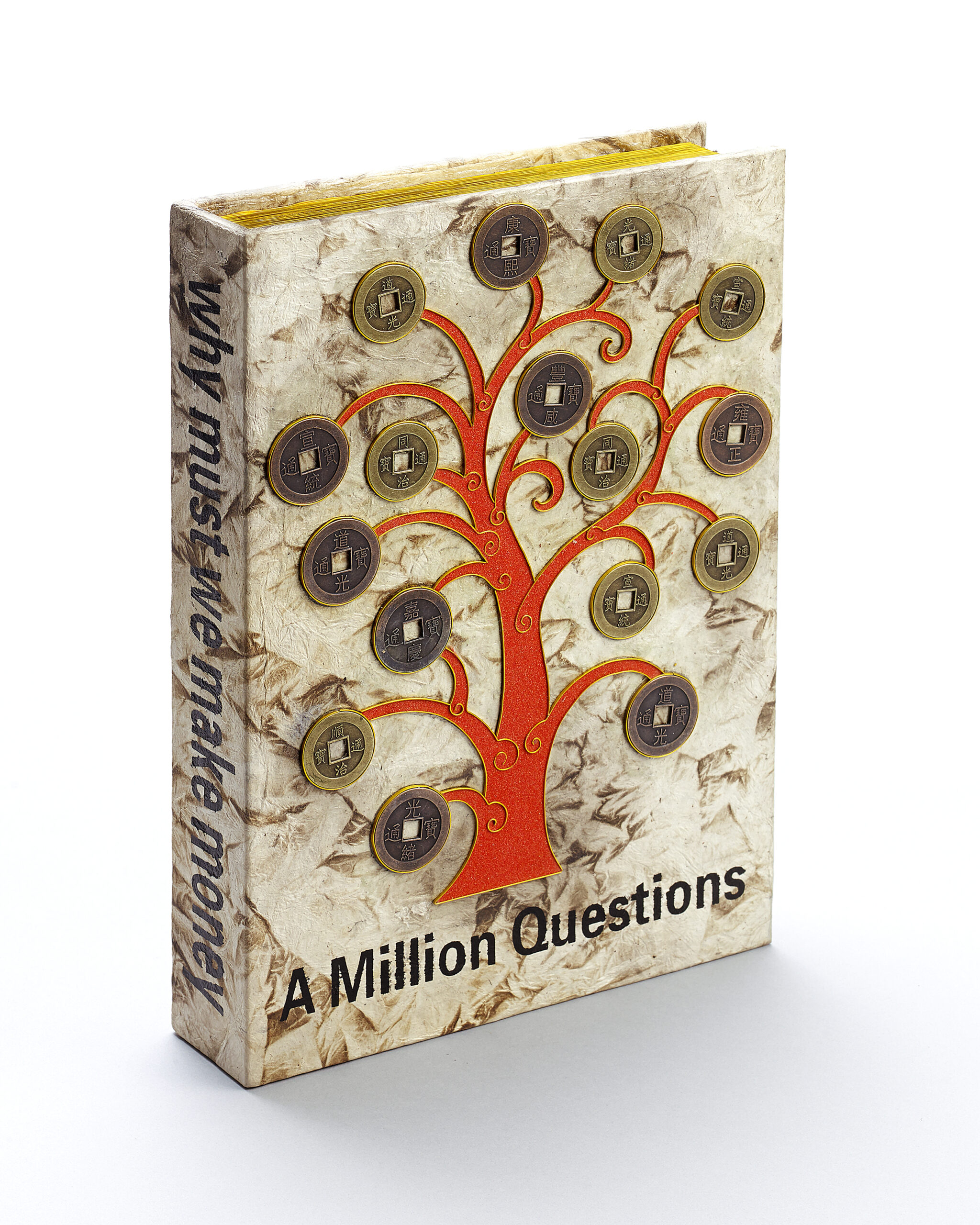

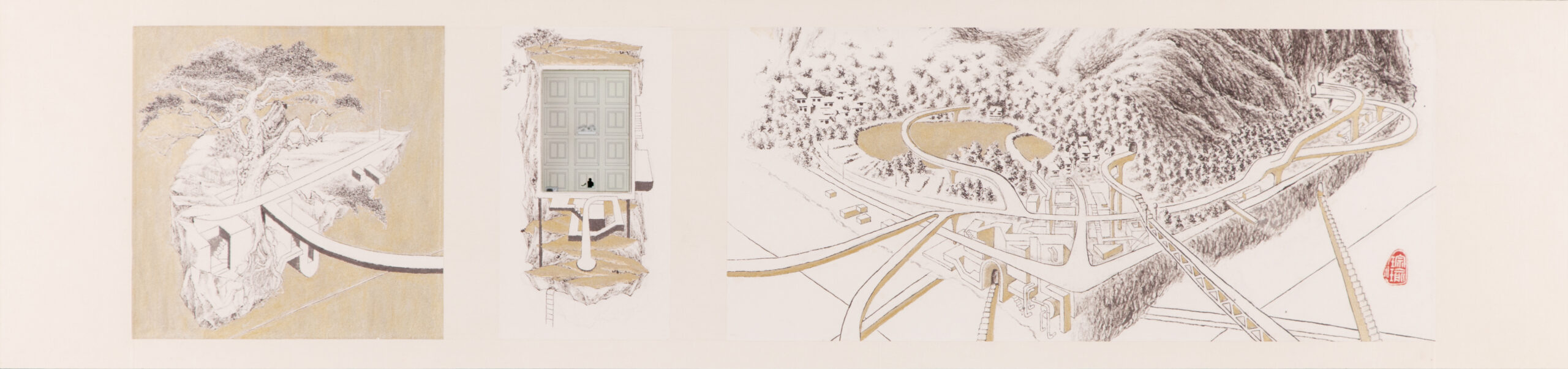

Hong Kong painter and new media artist Wong Chung-Yu’s meticulous articulations capture the dichotomy of extreme urbanism and urgent natural beauty that is at the core of Hong Kong’s duality. The Tibetan contemporary artists Gade and Nortse create art that is simultaneously bitter, beautiful and humourous. From Gade’s cloisonné books and painted scrolls to Nortse’s mandala assemblage, each artist makes deceptive use of traditional forms to reveal, on closer investigation, that what they are actually working with is both the material and conceptual detritus of global cultural encroachment.

Reverberating forward and backwards in time is a group of hand-carved and painted Tibetan sutra covers dating from the 13th-15th century, whose rich and reverential luminosity is offset by an abstract quality that reminds us how sophisticated abstract forms are as eternal and transcendent as nature, philosophy and experimentation itself.

CHENG Tsai-Tung

Moonlit Pines

2005

Ink and Colour on Paper

87 x 45 cm

Gade

Made in China

2007

Mixed Media on Paper

193 x 138 cm

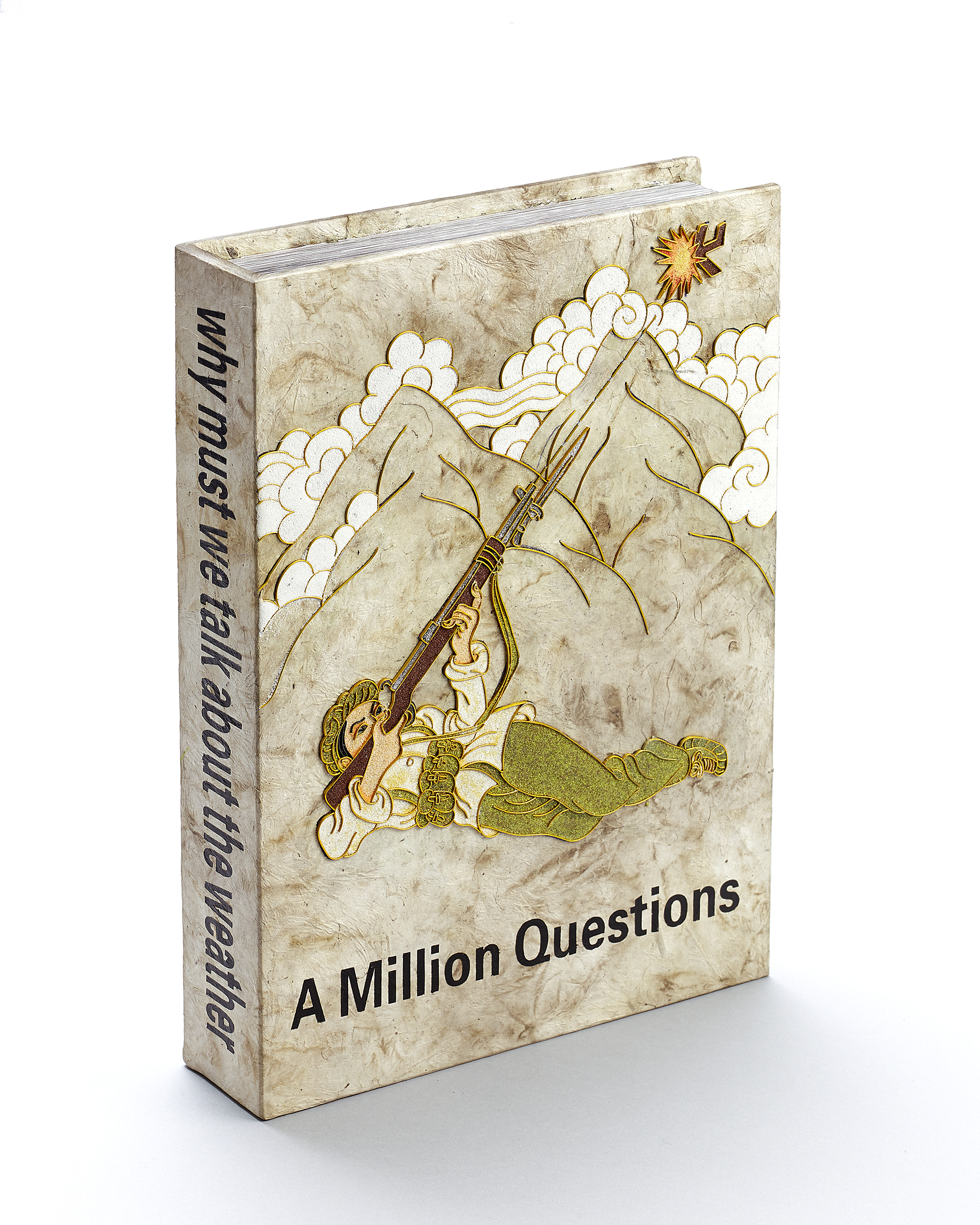

Gade

A Million Questions: why must we make money

2013

Wood, handmade Tibetan paper and cloisonné

29.7 x 21 x 5 cm

Image Courtesy of the Artist and Rossi & Rossi

Gade

A Million Questions: why must we talk about the weather

2013

Wood, handmade Tibetan paper and cloisonné

29.7 x 21 x 5 cm

Image Courtesy of the Artist and Rossi & Rossi

LIE Fhung

Life Force : Terrain 13

2015

Copper and mixed media

31 x 92.5 x 2.5 cm

LIE Fhung

Life Force : Terrain 12

2015

Copper and mixed media

31 x 92.5 x 2.5 cm

LIE Fhung

Life Force : Terrain 3

2014-2015

Tin and mixed media on copper

32 x 32 x 3 cm

LIE Fhung

Life-Force : Terrain No.4

2014-15

Copper and mixed media

31.5 x 31.5 x 2.5 cm

Image Courtesy of the Artist

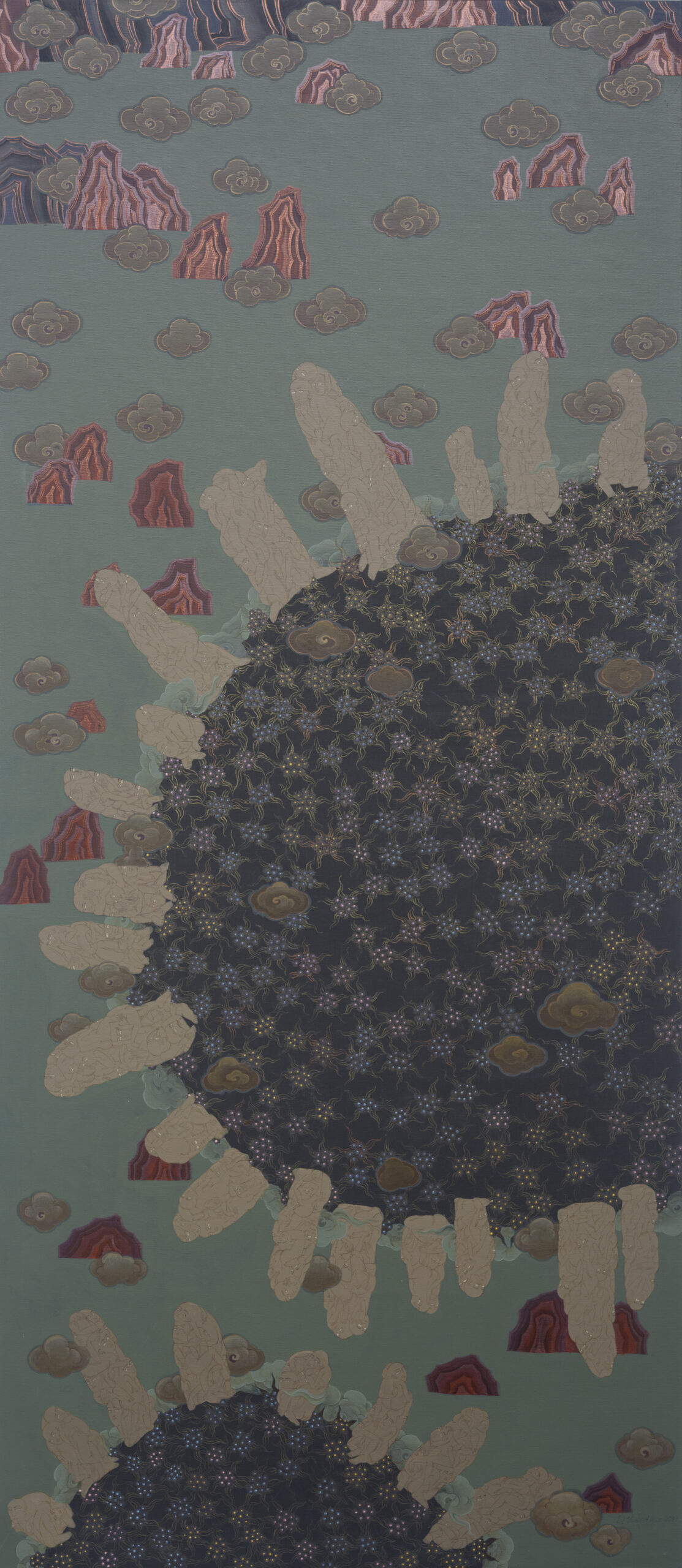

Dagvasambuugiin UURIINTUYA

13th Month

2011

Acrylic on canvas

160 x 70 cm

Dagvasambuugiin UURIINTUYA

Human Stones in Silence

2011

Acrylic on Canvas

115 x 130 cm

TSENG Yu-Ho

Shaolin Spirit: Steel Heart within the Softness

1999

Ink, acrylic, aluminum, dsui collage and handmade paper

Diptych: 76 x 76 cm each

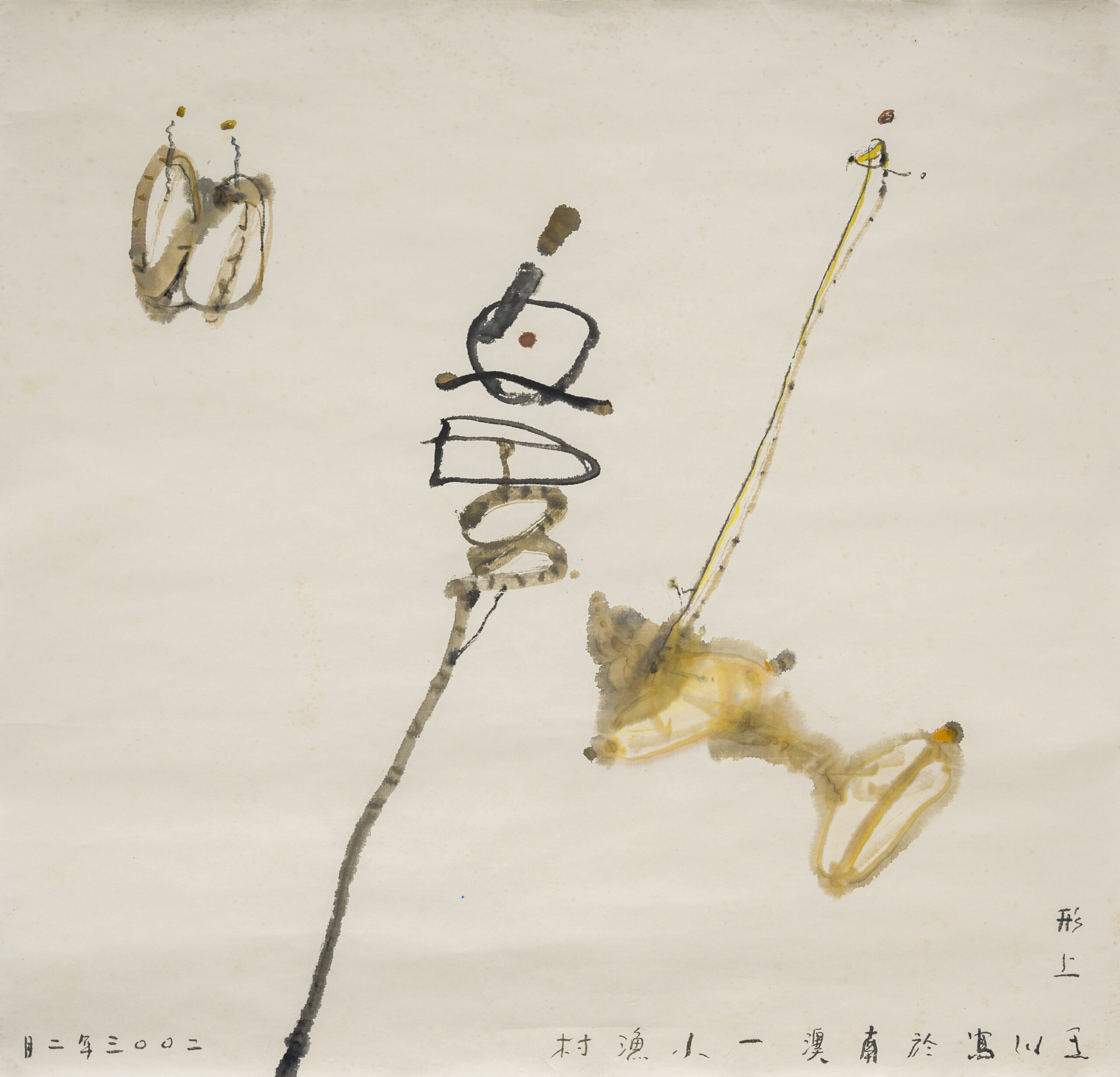

WANG Chuan

Golden Fish, Butterfly and Reeds

2003

Ink and Colour on paper

93 x 96 cm

WANG Dongling

Romantic Comedy

2013

33 x 66 cm

Ink on gold paper

XU Longsen

Mountain Mists No. 2

2013

Ink and Colour on Gold Paper

14 x 89 cm

Wong Chungyu

The Prosperous World I

2010

Mixed Media and Video Animation

39 x 157 x 11.5 cm

YAN Shanchun

Orioles Singing in the Willows No. 2

2005

Ink and Acrylic on Canvas

120 x 180 cm

YU Peng

Pleasures of the Garden

1993

Ink and Colour on paper

179 x 97 cm

YU Peng

Soul Roams in Pure Emptiness Spirit Transcends the Mundane World

1994

Ink on Paper

94 x 63.5 cm

FUNG Ming Chip

Untitled

1983

Carved Wood and Acrylic

111.5 x 110 x 2.8 cm

Anonymous Tibetan Artist

Manuscript Cover Tibet

13th-14th century

Carved, painted and gilded wood

25 x 73 x 3 cm

Mimi LIPTON

1.Bracelet

22ct gold, demantoid, Madagascar In collaboration with Ram Rijal

In collaboration with Ram Rijal