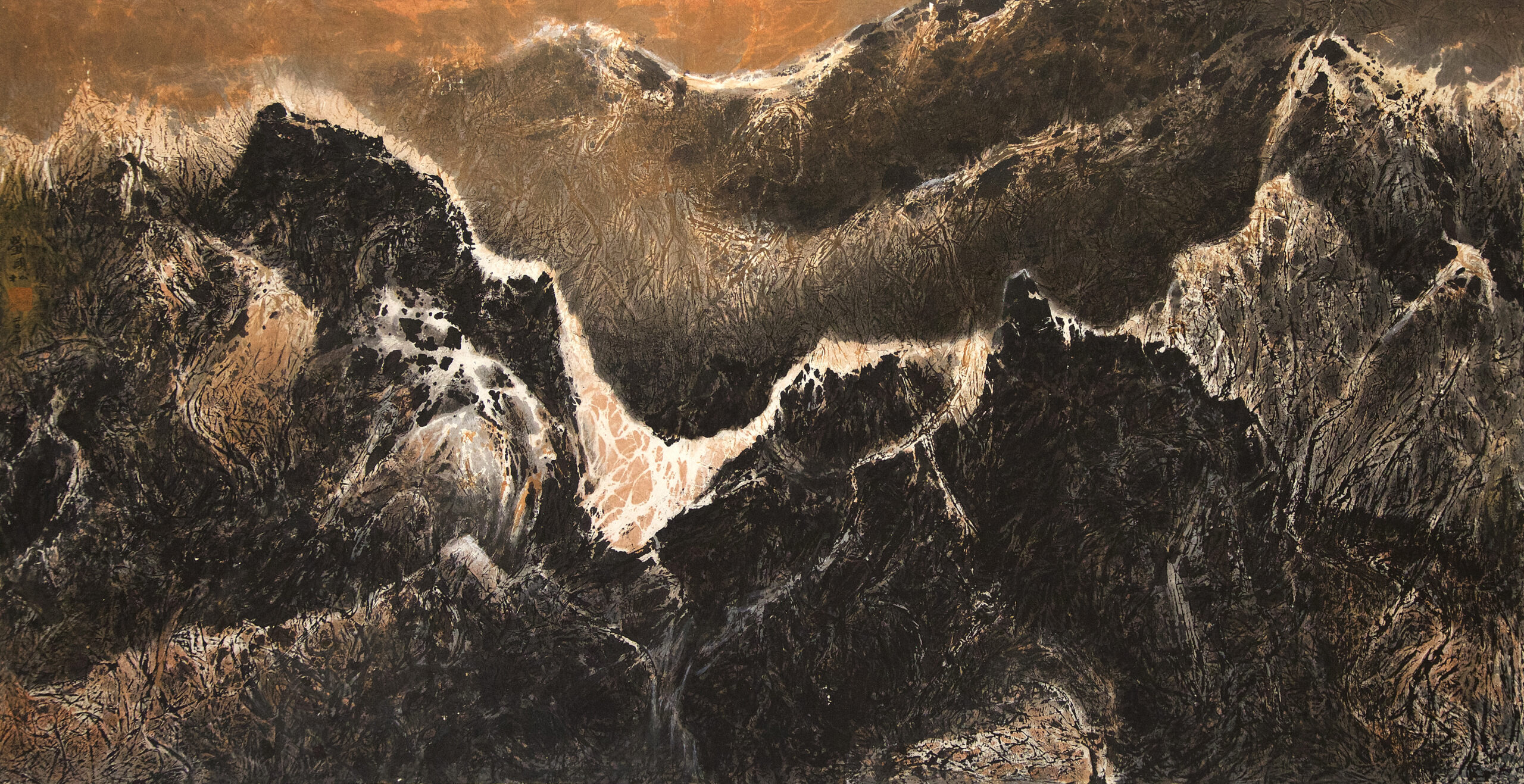

LIU Guosong (LIU Kuo-sung)

劉國松works in Taiwan (b. 1932, Anhui)

The Age of the “Maker”

Concerning discussion about “making “ (zhi-zhuo) art, we should review art history about traditional attitudes to “making” (zhuo). Early Chinese painters did not sign their works, and when they did the convention was to write “made (zhi) by so and so”; is this not done in the same spirit of ‘zuo’ as in ‘zhi-zhuo’? When strong mineral pigment painting became popular, signatures changed to “painted (hui) by so and so”. After ink painting started to spread, artists acknowledged the predominance of ink and signed “drawing (hua) by so and so”. With the coming of age of literati painting, signatures evolved into “written (xie) by so and so”. That was during the last stage in the development of Chinese painting; now we are at a new age. This is the age of “making”(zhuo) art.

From “Dissimilarity First, Refinement Later” (1999)

Painting is like Playing Go

The decline of Chinese painting is inseparable from its becoming progressively formulaic. Before Yuan dynasty (14th c) painters invented their own approaches to depicting rock texture and created their own ‘texture stroke’ (xun). Later artists ceased to look at real mountains and rivers, and also lost the urge to invent. The skill in copying old masters made them proud of the fact that they had “full grown bamboo in the heart”. But how much bamboo can one put in one’s heart? Of course the art would turn formulaic. I have a solution to this problem, which I call “paint as if it is a game of Go”. One goes a step at a time, like playing chess; one response to new situation at every move. One should not know how the painting is going to end up; if one did, then it would surely be stiff and lifeless.

From “On Creating Ink Painting and Teaching” (1996)

Imitating the New Does Not Displace the Old; Copying Western Art is No Better Than Copying Chinese Masters

I have always maintained that my ideal and purpose in innovating Modern Chinese Painting is a dual sword: “Chinese” and “modern” are the two edges of the blade. The blade hurts the “western style” artists as well as the “high traditionalists”. Traditional brush technique has long turned into fossils, and old set forms (landscapes, figures, birds and plants) become dried wells. I therefore must send them into the funeral parlour. However, imitating western art is equally hopeless. We don’t live in the Song and Yuan dynasties, nor do we live in European and American cultures. If it is fake to copy old masters, it is no different copying westerners. Copying western art is no better than copying Chinese masters. To be a modern Chinese artist one must create what has not been, neither in China nor abroad, and belongs only to China today.

From “The Way of Chinese Modern Painting” (1965)

Artists Need Experimenting As Much As Scientists Do

I always tell my students: It is no different being an artist than a scientist. A scientist has to be devoted to his laboratory experiments in order to come up with successful experiments and breakthroughs. A painter is no different; he must stick to his experiments in the studio, and the successful experiment leads to creative work that establishes him as a painter. If a person only knows to follow the brush mark of the ancients then he is no different than the scientist’s laboratory assistant! An assistant is there to attend to the scientist; he has neither inventions nor creative ideas.

From “On Creating and teaching Ink Painting” (1996)

Use the Vocabulary of Today and Use An Individual Grammar

People who do not truly understand technique cannot grasp the nature of painting; those without technique cannot possibly become real artists.

No matter which type of painting, its foundation lies in the repeated practice of technique; the achievement in other techniques is not going to help. That is to say, however well one copies a Song painting, however skilful one is in traditional brushwork, one only remains a traditional literati painter, because these are not the foundation of modern ink painting. People would object to this claim and say that painting is not just technique, it is also about spiritual content! True; but a modern spiritual content has to be expressed with modern vocabulary, a personal spiritual content must be expressed with individual articulation. If one picks up the remnants of old masters, repeating what has been said a thousand times, how can one speak of the spirit? Every period has its own spirit of the time, its own vocabulary and individual grammar; one must learn to grasp this before one can articulate one’s inner voice. As far as technique goes, there is no other way than repeated practice; it is a prerequisite to individual expression.

From “On Creating and Teaching Ink Painting” (1996)

The Point of Abstract Expression Should be Direct

Cheerfulness is a mood, mood is an abstract spiritual activity. Any spiritual activity such as this has no other of expressing than in an abstract form. That is why even in the Song dynasty the master Guo Xi would say: “Recent painters who paint the subject of taking pleasure in the mountains would show an old man at a peak, when the subject is taking pleasure in water the subject would be a man by a cliff. This is truly limitation; how can pleasure be portrayed (xing-zhuang) by just one figure.” Qing dynasty painter Zhou yigui had the same feeling: “People say it is impossible to paint the purity of snow, the brightness of the moon, the fragrance of flowers and the feelings of figures. That is because one cannot arrive at that which is abstract (xu) with form (xing).” Therefore, if we can expressive directly the feelings of happiness and sadness with several patches of bright colour and swift lines, or dim colours and frail lines, why do we need to borrow indirect means such as the muscular structure of a face? Expressing directly is definitely closer to the truth than expressing indirectly.

From “About Abstract Painting” (1962)

Content and Form are Two Side To the Same Matter of Art

Unfortunately, the usual response to painting is to seek the story or ask the painter what he intends to say. Rather than criticising this as the misinterpreting of art, it is more suitable to say it is ignorance of what content means. Any artist pursues his individual artistic style, and the pursuits of style include that of content. When I first encountered Song dynasty master Fan Quan’s “Travellers in the Mountains” I was so impressed that all my hair stood up. What is the content of this painting? Is it the majesty of Zhongnan Mountain? Is it the insignificance of man in nature? Or the pleasures or pains of travelling? No. It is the powerful sensation imparted by the form of Fan Quan’s creativity, what theorists variously call “spirit”, “spiritual realm” and “rhythm of energy”. Form and content appear to be two opposing ideas, but in fact they are the two side to the same subject, they are inseparable. An imitator of Fan Quan that lacks creativity and personal feeling has form and no content; furthermore, even the form is not his, so it is as good as saying there is no form. This is insignificant as art and a waste in terms of art history. As the writer Walter Pater said long ago that all art approach music, because in music form and content are one and the same.

From “On the Content of Painting and Art Appreciation” (1991)

“Brush and Ink” Translated Into Plain Talk Is “Point, Line, Surface, Colour”

What does one mean by “bi and mo (brush and ink)”? “Bi (brushwork)” refers to traces left on the paper by movement of the brush; “mo (ink-work)” is the effect of ink absorbed into the paper. In today’s language, “brushwork” is “point and line”, “ink-work” is “colouring and surface”. As a painting was traditionally created in ink with brush, we say its “brushwork” is good when it has done well with “point and line”, and good “ink-work” when its “colouring and surface” are good.

Now let us demystify “xun (texture strokes)”. What is it? Southerners may not know it, but it is obvious to northerners. In winters, people who work in the cold get creases and chaffs on the skin due to the weather. “Xun” is simply skin texture; Chinese artists do well to release themselves from the “hemp xun” that has bound them! One doesn’t necessary need to create “texture” with the brush, especially not to “write (paint)” it. “Texture” can be achieved with an instrument, and the “leave vein xun”, “fish-net xun”, “peal drop xun”, “ripple xun” and “flowing sand xun” of contemporary ink painting are all done with means other than a brush; this has enriched the expressiveness of Chinese painting and greatly expanded its range.

From “Concepts of Chinese Painting Today” (1988)

Creativity is Always Controversial

Not only do artists and connoisseurs often fall into the traps of traditionalism and get stuck, it happens to art critics as well. When Impressionism and Fauvism appeared in the salons of Paris, numerous famous critics attempted to fit their works into the confines of principle of art from the past. When they found the works did not fit, they turned around to attack the artists. When the new art get established as a trend, the artists could do nothing but to develop new theories and principles based on the works. Chinese ancients said “Renew daily your virtues”. This should be a motto for creative art; artists who rebel against stagnant traditions and strict rules, artists who do not wish to pick up the debris of predecessors and create works that are as easily understood as forgotten, they must have independent ideas, original styles and particular ways to express them.

From “About Connoisseurship” (1972)

The Ideal of Communing with Heaven

The various techniques of “splash ink”, “blown clouds”, “scattering chewed sugar care” are all “semi-automatic” techniques aimed at chance effects.

Chinese philosophy of life is different from the West: in the West there is the faith in controlling the heavens, whereas Chinese believe man is part of nature and the goal of human culture is to achieve harmony with nature. The highest ideal for Chinese culture is to commune with Heaven. If we take this as the goal of painting, the chance effects of “semi-automatic” techniques mentioned above may be looked upon as the natural effects that provide the ground for the artist’s imaginative elaboration. The spirited rhythm resulting from this approach is what the ancients aspire to, and it is also what we now aspire to.

From “On Creativity and Teaching of Ink Painting” (1996)

The Chinese is a People of Abstract Art

The Chinese is in fact a people most appreciative of the beauty of abstraction. This is not only seen in our visual arts, it is also visible in the way we live. Everyone admits that calligraphy is “abstract” art, and this aesthetics has direct bearing on the development of abstract art in the modern world internationally. In Chinese theatre, all the stage actions are depicted “abstractly”, with stylized movements symbolizing crossing a door, mounting a horse, rowing a boat. By contrast, in European opera the use of realistically portrayed stage set often extend to employing real artifacts and real animals. If we look around the world of a Chinese, we see this spirit of abstraction everywhere. The scholar’s rock for the garden or the studio is the earliest abstract sculpture; then we have also root-sculpture, “panzhai”(potted plants). The Chinese passion for rocks is legendary, we have a connoisseurship for its shape, its colour and texture, and for centuries marble sheets have been framed as “painting” on tabletops, back of chairs and wall decoration. Today when one speaks about abstract art it is invariably assumed to be Western and foreign, therefore in comprehensible. This is definitely unjustifiable.

From “On the Connoisseurship and Criticism of Abstract Ink Painting” (1999)

First Individuality, Then Quality

The education of Chinese painting is based on the principle of “learning resembles the building of a pyramid”, therefore teaches always emphasis the need for a solid foundation, believing that the broader the base the tall one can build on it. In other words, one must first study the styles of past masters and do it well before pursuing one’s own creative ideas. I call this principle: “first quality, then individuality”. It is as Master Li Keran said: “Enter with maximal endeavour, then exit with maximal courage”. What does one enter into? Tradition, of course. It is easy to enter into tradition, to leave is not so easy.

On account of this and years of practical teaching, I propose instead: “first individuality, then quality”. I want to liberate literati painting from its feudal strappings by introducing new technical approaches to my students and encouraging them to investigate new technical solutions of their own. After repeated practice of their personal techniques, they will be able to establish a personal style.

Speaking of foundations, which modern skyscraper has a foundation broad enough to match its height? Modern architecture drives its foundation deep down, not broad on the ground, in order to support its soaring height. By the same argument, modern painting does not excel on the range of subjects techniques, but on its individuality and quality. The more original the technique, the higher it may soar. This is what I mean by: “first individuality, then quality”

From “Eastern Aesthetics and Modern Art”

| 1932 | Born in Bangbu, Anhui, China |

| 1949 | Move to Taiwan with Nanjing Revolutionary Army Orphan School |

| 1951-1955 | Studied in Fine Arts Department of National Taiwan, Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan |

| 1996-1999 | Head of the Fine Arts Research Institute at the Tainan, National University of the Arts, Tainan, Taiwan |

| Now Lives and Works in Taiwan | |

Selected Solo Exibition

| 2013 | LIU Guosong, Hanart TZ Gallery, Hong Kong |

| 2012 | A Man of East, West, South, North — Liu Kuo-Sung 80th Birthday Retrospective Exhibition, National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Taiwan |

| 2011 | Art Exhibition by Liu Guosong – A 80-year Retrospective, National Art Museum of China, Beijing, China |

| 2010 | The Universe in My Mind: Liu Guosong 60 Years Retrospective Exhibition, Modern Art Gallery, Taichung, Taiwan |

| The Universe in My Mind: Liu Guosong 60 Years Retrospective Exhibition,, Michael Goedhuis Gallery, London, UK | |

| The Universe in My Mind: Liu Guosong 60 Years Retrospective Exhibition, New Taipei City Gallery, New Taipei City, Taiwan | |

| 2009 | The Universe in My Mind: Liu Guosong 60 Years Retrospective Exhibition, Hubei Provincial Museum, Wu Han, China |

| The Universe in My Mind: Liu Guosong 60 Years Retrospective Exhibition, Three Gorges Museum, Chingquing, China | |

| The Universe in My Mind: Liu Guosong 60 Years Retrospective Exhibition, Ningxia Museum, Ningxia, China | |

| The Universe in My Mind: Liu Guosong 60 Years Retrospective Exhibition, YaMing Art Gallery, Anhui province, China | |

| The Universe in My Mind: Liu Guosong 60 Years Retrospective Exhibition, National Dr. Sun Yet-sen Memorial Hall, Taipei, Taiwan | |

| The Universe in My Mind: Liu Guosong 60 Years Retrospective Exhibition, The University Museum and Art Gallery of the University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong | |

| 2008 | Solo Exhibition, Galerie 75 Faubourg, Paris, France |

| 2007 | The Universe in the Mind: 60 Years Painting by LIU Guosong, National Palace Museum, Beijing, China |

| The Universe in the Mind: 60 Years Painting by LIU Guosong, Shanghai Art Museum, Shanghai, China | |

| The Universe in the Mind: 60 Years Painting by LIU Guosong, Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou, China | |

| 2006 | The Universe in the Mind: A Retrospectiveof LIU Guosong at 70, Hunan Provincial Museum, Changsha, China |

| The Universe in the Mind: A Retrospectiveof LIU Guosong at 70, Zhejiang Museum, Hangzhou, China | |

| 2005 | The Universe in the Mind: A Retrospectiveof LIU Guosong at 70, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan |

| The Universe in the Mind: A Retrospectiveof LIU Guosong at 70, Singapore Tylor Print Institute, Singapore | |

| 2004 | The Universe in the Mind: A Retrospectiveof LIU Guosong at 70, Taiwan Exhibition Tour organized by Taiwan Soka Association |

| The Universe in the Mind: A Retrospectiveof LIU Guosong at 70, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong | |

| 2003 | The Universe in the Mind: A Retrospectiveof LIU Guosong at 70, Hanart TZ Gallery, Hong Kong, China |

| The Universe in the Mind: A Retrospectiveof LIU Guosong at 70, Shangdong Qingdao Museum, Shangdong, China | |

| 2002 | The Universe in the Mind: A Retrospectiveof LIU Guosong at 70, Accton Arts Center, Hsinchu, Taiwan |

| The Universe in the Mind: A Retrospectiveof LIU Guosong at 70, History Museum, Beijing, China | |

| The Universe in the Mind: A Retrospectiveof LIU Guosong at 70, Shanghai Art museum, Shanghai, China | |

| The Universe in the Mind: A Retrospectiveof LIU Guosong at 70, Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou, China | |

| 2001 | Chengdu Contemporary Art Museum, Chengdu, Sichuan, China |

| 2000 | Art Center, National Central University, Taiwan |

| Goehuis Contemporary, New York, USA | |

| 1999 | National Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hall, Taiwan |

| 1998 | Modern Art Gallery, Taichung, Taiwan |

| 1997 | He Xiangning Art Museum, Shenzhen, China |

| Modern Art Gallery, Taichung, Taiwan | |

| 1996 | National Museum of History, Taipei, Taiwan |

| G.Zen 50 Art Gallery, Kaohsiung, Taiwan | |

| 1994 | Lung Men Art Gallery, Taipei, Taiwan |

| 1992 | National Museum of Art, Taichung, Taiwan |

| 1990 | Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Taiwan |

| 1989 | Ubersee-Museum, Bremen, Germany |

| 1988 | Weifang Museum, Weifang, Shangdong, China |

| 1987 | National Painting Museum of Hunan Province, Changsha, Hunan, China |

| University Art Gallery, Shanxi University, Taiyuan, Shanxi China | |

| 1986 | Art Gallery of Shanxi Artists Association, Sian, Shanxi, China |

| Youth Palace, Lanzhou, Gansu, China | |

| Urumqi City Exhibition Hall, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China | |

| Cultural Palace, Chongqing, Sichuan, China | |

| University Art Exhibition Hall, Southwest University, Chongqing, Sichuan, China | |

| 1985 | Hong Kong Arts Centre, Hong Kong |

| Museu Luis de Camoes, Leal Senado de Macau, Macau | |

| 1984 | Shanghai Museum of Art, China |

| Shangdong Provincial Art Gallery, Jinan, China | |

| Zhejiang Exhibition Hall, Hangzhou, China | |

| Yantai City Exhibition Hall, Yantai, Shangdong, China | |

| Fuzhou May 1st Plaza Central Hall, Fuzhou, China | |

| 1983 | National Museum of Fine Arts, Beijing, China |

| Jiangsu Provincial Art Museum, Nanjing, China | |

| Heilongjiang Provincial Art Gallery, Harbin, China | |

| Hubei Provincial Art Exhibition Gallery, Wuhan, China | |

| Guangdong Art Institute Gallery, Guangzhou, China | |

| 1982 | Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Logan, Utah, USA |

| 1981 | Columbus Cultural Arts Center, Columbus, Ohio, USA |

| UMC Fine Art Gallery, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA | |

| Galerie Andree, Costa Mesa, California, USA | |

| 1980 | Ulrich Museum of Arts, Wichita, Kansas, USA |

| University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA | |

| Monterey Peninsula Museum of Art, Monterey, California, USA | |

| Museum of Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, USA | |

| 1979 | Play House Art Gallery, Canberra, Australia |

| Museum fur Kunsthandwerk, Frankfurt, Germany | |

| 1978 | East and West Art Gallery, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia |

| Greenhill Galleries, North Adelaide, South Australia | |

| Churchill Gallery, Perth, Western Australia | |

| 1977 | Plymouth State College Art Gallery, University of New Hampshire, Plymouth, New Hampshire, USA |

| Occidental College Art Gallery, Los Angeles, USA | |

| 1976 | Ulrich Museum of Arts, Wichita, Kansas, USA |

| Museum of Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, USA | |

| 1975 | Colorado Springs Fine Arts Centre, Colorado, USA |

| M.M. Shinno Gallery, Los Angeles, California, USA | |

| 1974 | Laky Gallery, Carmel, California, USA |

| 1973 | Hong Kong Art Centre, Hong Kong |

| San Diego Museum of Art, California, USA | |

| Frank Caro Company, New York, USA | |

| 1972 | Art Museum at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA |

| Utah State University Art Gallery, Logan, Utah, USA | |

| Brigham Young University Museum, Provo, Utah, USA | |

| Galerie Hans Hoeppner, Hamburg, Germany | |

| 1971 | Museum fur Kunsthandwerk, Frankfurt, Germany |

| Hugh Moss Ltd., London, England | |

| Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, England | |

| 1970 | Museum fur Ostasiatische Kunst, Koln, Germany |

| Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, USA | |

| San Diego Museum of Art, California, USA | |

| 1969 | The Dallas Center for Contemporary Art, Texas, USA |

| National Museum of History, Taipei, Taiwan | |

| St. Mary’s College Art Gallery, Nortre Dame, Indiana USA | |

| 1968 | The Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, Washington, USA |

| The Taft Museum, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA | |

| The Luz Gallery, Makati, Rizal, The Philippines | |

| 1967 | Lee Nordness Galleries, New York, USA |

| Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Missouri, USA | |

| Georgia University Art Gallery, Athens, Georgia, USA | |

| 1966 | Laguna Beach Museum of Art, California, USA |

| Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA | |

| 1965 | Taiwan Museum of Art, Taipei, Taiwan |

| Selected Group Exhibitions | |

| 2015 | Magical Mountains: Hanart TZ Gallery at Art Basel HK 2015, Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre, Hong Kong |

| 2014 | “HANART 100: IDIOSYNCRASIES” Celebrating Hanart 30th Years, Hanart TZ Gallery, Hong Kong / Hong Kong Art Centre, Hong Kong |

| Abu Dhabi Art 2014 Exhibition, Abu Dhabi, UAE | |

| 2012 | Vision – Soka Art 20th Anniversary, Soka Art Center, Taipei, Taiwan |

| Tensions of White Linear – Ink Painting Exhibition of Chinese Mainland, Hongkong and Taiwan, Art Center of National Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu, Taiwan | |

| Century Development·Inspiring Painting —— Arts Painting Exhibition for Centenial Anniversary of the Revolution of 1911, National Art Museum of China, Beijing, China | |

| 2010 | Chinese Character Festival, Taimiao, Beijing, China |

| 2009 | New Year Print Joint Exhibition, Art Center of National Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu, Taiwan |

| 2008 | Inkism, Shangshang Art Museum, Beijing, China |

| 2007 | Encre de Chine : Nouvelles Tendances LIU Kuo-Sung et LEE Chun-Yi, le Maître et l’élève, Galerie Leda Fletcher, Geneve, Switzerland |

| 2005 | Paintings by Liu Guosong and his Students, Arizona State University, Arizona, USA |

| 2001 | China Without Limits, New York, USA |

| 2000 | Gate of the New Century, Chengdu Art Museum, Chengdu, China |

| 1999 | Paintings of Five Contemporary Chinese Artists, National Art Museum of China, Beijing, China |

| 1998 | China: 5000 Years, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City, USA |

| China: 5000 Years, Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, Spain | |

| Expectation 2000: Chinese Modern Art Exhibition, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany | |

| Shanghai Biennale, Liu Hai Su Art Museum, Shanghai, China | |

| 1997 | Chinese Art, Shanghai Art Museum, Shanghai, China |

| 1995 | Taiwanese Contemporary Ink Painting Exhibition, Taiwanese Cultural Representative Office, Paris, France |

| Gwangju Biennale, Kwangju City Art Museum, Korea | |

| 1989 | The Fourth Asian International Art Exhibition, Seoul Metropolitan Museum of Art, Korea |

| 1988 | The Third Asian International Art Exhibition, Fukuoka Art Museum, Japan |

| Oriental Color & Ink Painting’s Exhibition, Korean Art Gallery in Seoul, Korea | |

| 1987 | Contemporary Chinese Painting Exhibition, Vancouver Art Gallery, Canada |

| Chinese Modern Painting Exhibition, Brussels City Hall, Belgium | |

| Exhibition of International Art of Suiboku, Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, Japan | |

| 1986 | Modern Asian Ink and Color Paintings Exhibition – 10th Asian Games Arts Festival, Korean Culture Center, Seoul Korea |

| May Painting Salon, Grand Palais, France | |

| 1984 | 20th Century Chinese Paintings Exhibition, Hong Kong Art Museum, Hong Kong |

| Sixth National Art Exhibition, The National Art Museum, Beijing, China; Shaanxi Artists Association Gallery, Xi’an, China | |

| 1982 | Contemporary Hong Kong Art, Metropolitan Museum of Manila, Philippines |

| 1981 | Peinture Chinoises Traditionnelles, Musée Ceruschi in Paris, France |

| The Inauguration of Chinese Painting Research Institute, Exhibition tour in China. | |

| The First Exhibition of Asian Art, Bahrain City, Bahrain | |

| 1979 | Artists ’79, General Assembly Building of the United Nations, USA |

| 1978 | British Commonwealth Print, Art Museum at University of Alberta, Canada |

| 1977 | Hong Kong Art Today, Hong Kong Art Museum, Hong Kong |

| 1975 | 11th Asian Contemporary Art Exhibition, Ueno No Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan |

| 1974 | Contemporary Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, Yale University Art Gallery; Exhibition tour at various museum and galleries in USA |

| 1973 | Fifth Moon Group’s Exhibition, Denver Art Museum, Colorado, USA |

| International Art Exhibition, organized by ITT, tour at major museums | |

| 1971 | Fifth Moon Group’s Exhibition, Honolulu Museum of Art, USA |

| Fifth Moon Group’s Exhibition, The Taft Museum, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA | |

| 1970 | Calligraphic Statement, The Arts Club of Chicago, USA |

| 1969 | The Development of 20th Century Chinese Painting, Stanford University Art Museum, USA |

| 1965 | China Modern Art, Galleria del Palazzo delle Exposizioni in Rome, Italy |

| Asia Pioneer Artist, exhibition tour in 10 cities in Asia | |

| 1964 | Modern Chinese Paintings, Exhibition tour in 14 Counties in Africa |

| 1961 | Paris Youth Bienale (1961, 1693, 1969, 1971), Musée D’Art Moderne de La Ville de Paris, France |

| 1959 | Sao Paolo Bienal, Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Brazil |

| 1957 | Young Asian Artists, Tokyo, Japan |

| Fifth Moon Group’s Exhibition (1st), Taipei Zhongshan Hall, Taiwan(Organize once in Taipei every year) | |